We have come up with a solution that is really, really, I think very good. Now I have to tell you, its an unbelievably complex subject, nobody knew that healthcare could be so complicated.

– US President Donald Trump, demonstrating how the incompetent lack the cognitive tools to understand their own shortcomings or accurately assess others.

There are many scenarios in our business or personal lives in which we need to evaluate the competence of another person. This might be an investor evaluating a financial advisor, a recruiter interviewing a candidate, a voter choosing a politician, a consumer judging a salesperson or one of any number of other scenarios. In these cases, the evaluator will lack detailed knowledge of the particular subject area, which would mean that they, (like President Trump) do not have the ability to distinguish competence. Without being able to distinguish competence, studies have shown that evaluators of advice will fall back on confidence which is only loosely correlated with actual ability. So until such time as informaton about the accuracy of the advisor is made clear, confidence will rein over competence for the layperson’s thinking.

The starting point for our little journey is the Dunning-Kruger effect. As posited by Dunning and Kruger in their 1999 paper, this holds that people who are incompetent in a particular subject area do not possess the skills to recognise their own incompetence and so vastly overrate their skills. Although it is not the focus of the paper, the third study shows that these incompetent folks also lack the ability to recognise ability in others. It is important to note that this doesn’t apply for all skills, but particularly those where knowledge of the skill confers competence. This shouldn’t matter for the intellectual areas we are considering, but it does explain why I have no illusions of being an NBA basketballer, for instance.

Now where this gets interesting is if we consider a layman or someone with little skill in a particular subject area. They will, by virtue of their lack of expertise, have a similar paucity of ability to identify skill in themselves, or importantly for our case, in others. So when they consider advice from a specialist advisor, they will not be able to identify accurately the competence of the advisor. Keep this in mind as we switch gears.

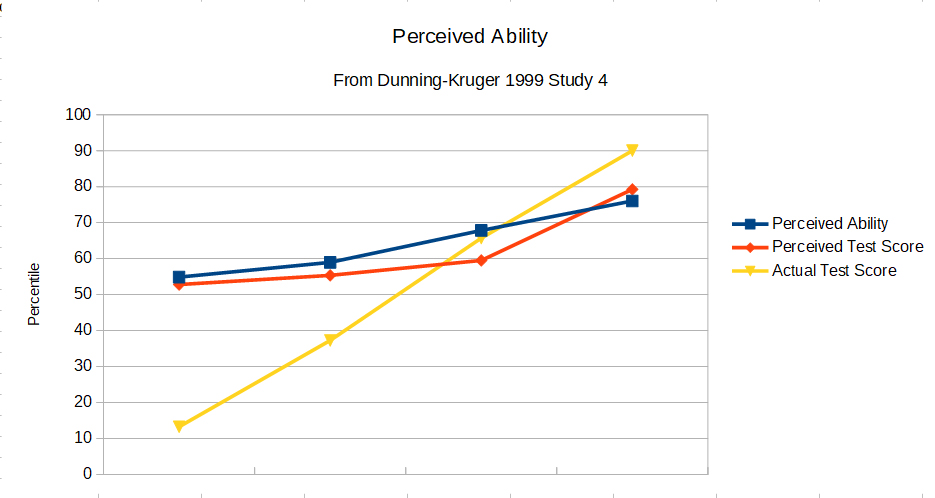

There has been some interesting recent work on how we evaluate advisors. Sah et al build on the work of Price & Stone in evaluating the role of confidence in this decision. Per this research, if the accuracy of an advisor can be readily determined via feedback, then this is the predominant factor in evaluating credibility. If however determining accuracy is expensive or not possible, then an advisor’s confidence is the primary driver of their credibility, acting as a proxy for accuracy. If the layman doesn’t have the skill to judge the advisor’s ability directly, then the only way they can evaluate their accuracy is by taking another expert’s advice (which he will also be unable to properly evaluate) or by waiting for a sufficient store of data to developed. The results from Anderson et al show that after 7 weeks, overconfidence is still a strong predictor of perceived competence, so this data collecting period will take substantial time. As such, the layman will end up using confidence as a proxy for ability for the bulk of evaluations. Now you can probably see where I’m going with this, take another look at that graph from Dunning-Kruger. An individual’s own ability doesn’t have that much influence on their perception of their ability (and thus confidence in that ability). There appears to be a small correlation, depending on which study you read, but across a population there are a whole bunch of factors which influence confidence and can readily overwhelm that small effect.

The work from Anderson et al expands on this, showing that overconfident individuals display competence signalling cues such as speaking more, using a factual and confident tone, providing more relevant information and offering answers first. These cues are used by observers to infer competence, yet there is no correlation between actual competence and use of these cues!

Overconfident individuals behaved in ways that conveyed competence more convincingly than did individuals who are actually competent.

Lets put this into context first with some examples where a person lacking subject specific knowledge might be given advice and lack the data to evaluate the accuracy of that advice. Politics comes immediately to mind, with a voter trying to evaluate the credibility of political leaders across all the areas which come with governing a country. The voter might have seen that particular leader once or twice before at past elections (though not in Australia!), but performing a proper evaluation of their past performance is a substantial effort and requires subject-specific knowledge around economics, policy outcomes, etc. Recruiters looking to fill technical positions need to evaluate candidates based on minimal information and often have expertise in recruiting rather than the subject-specific knowledge required to evaluate candidates accuracy. A layman looking to invest his money with a financial advisor lacks the knowledge of markets and finance to accurately evaluate the advice he is given, though in this case past performance may be used to provide some input into an advisor’s past accuracy, if the layman has sufficient knowledge to understand this.

A layman walking into a Harvey Norman store will probably lack the subject-specific knowledge to evaluate the advice given by the salesperson (as a knowledgeable person would be buying elsewhere). This can readily be extended to journalists in reasonably arcane areas such as finance and politics, whose abilities cannot necessarily be accurately evaluated by the layman reader. A business manager will build sufficient data to evaluate their subordinates eventually, but will probably rely on confidence initially, particularly if managing staff outside of their area of expertise. When working in mutli-disciplinary teams each member will by necessity evaluate their colleagues using confidence, lacking the technical ability to accurately evaluate their counterparts. A patient will not have the expertise to evaluate their doctor, and so will rely on the doctor’s confidence. So there are a whole bunch of areas where this effect holds true. I’m sure you can think of more for yourself.

There are many factors of personality and circumstance which can induce overconfidence beyond a person’s actual competence, for instance:

- Narcissism is a significant predictor of overconfidence (per Campbell et al)

- Extraversion is a significant predictor of overconfidence (per Schaefer et al)

- The link between the need for dominance and overconfidence is substantial (per Anderson et al)

Overconfidence also leads individuals to have a bigger influence on group discussions and a higher perception of competence. In fact, overconfidence leads to a higher social status in both short and long term groups. This feeds in to itself, as the desire for social status in turn promotes overconfidence.

Considering a particular case, recruiters excessively overrate the impact of candidate performance in interviews on job performance. Impressions of ability formed through interviews would appear to be a prime example of the above use of confidence as a proxy, even in the face of more accurate evidence of competence through tests. I’ve been digging into the literature on recruitment decisions that flows on from this, and have decided that they really warrant a separate post. So you’ll have to wait for that one.

Lets look at a couple of real world examples from the world of politics to demonstrate the power of advisor confidence, particularly when evaluated by unskilled laymen. The UK’s Brexit referendum pitted a confident Leave campaign against an uncertain Remain campaign, which demonstrates the persuasive power of confidence. Later, the US 2016 election was contested between Donald Trump who used confidence as a cover for his incompetence and the less confident Hillary Clinton.

I’d put myself in the upper half of the five to ten, so you’d be looking at seven, seven and a half.

– UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn rates his enthusiasm for remaining in the EU out of ten

The Brexit referendum put a complex, multifaceted decision in the hands of the British public. These laymen (in general) could not have enough knowledge in the legal, economic and geopolitical spheres to evaluate the expertise of their media and political advisors accurately. As this was a new proposal, there was no past history to aid in the decision evaluation process. The Leave campaigners comprising Tory and UKIP politicians came out with confidence that leaving the EU would have great benefits for the UK. They even painted their confidence onto the side of a bus.

However, the Remain side could not muster the same levels of confidence. A marriage of convenience between Tory, Labour and Lib Dem politicians could not sell the status quo as an amazing result. Labour under Corbyn tried to argue that the EU was a bit shit, but that they would be better off remaining inside and agitating for reform. This may have been an accurate evaluation showing competence, but the messaging lacked confidence and so didn’t cut through to the laymen voters.

The Leave side worked to undermine the impact of nuanced expert advisors, asserting that people had had enough of experts. This worked to further muddy voters ability to deduce accuracy in advisors and strengthened the hand of the tabloid press, whose confidence cut through. As a result, the confident message of Leave was successful despite the protestations of more competent experts.

He was an academic genius, and then they say, there’s Donald Trump, an intellectual, trust me, I’m like a smart person.

– US President Donald Trump, demonstrating how he is, like, a smart person.

The latest US election presents another scenario on which to examine our theory. Donald Trump is a classic example of someone who doesn’t have the competence to realise his own failings. Running the world’s leading superpower is work which requires skill across a range of intellectual disciplines in order to achieve your policy outcomes. The laymen who vote to evaluate a candidates suitability do not (generally) have the depth of knowledge in this domain to accurately judge a candidate’s competency. However, in this case the candidates normally have a track record of achievement across government, whether as senators, governors or in other elected positions. This track record can normally be used by voters to provide a guide to the candidate’s suitability, though this incomplete information does require effort on the part of the voter so simple candidate confidence is still a factor.

President Trump however has no such track record, having never held an elected office before the Presidency. This means that his own confidence plays a stronger role in voters estimations of his competence. And confidence is something Mr Trump has no shortage of. So to bastardise the quote from Anderson et al posited above, the overconfident Trump behaved in ways that conveyed competence more convincingly than did Clinton, who was actually competent. And as the voters lacked the skills to accurately judge his level of competence, Trump’s overconfidence was enough to convince them of his capability.

So screw actually being capable, confidence is the key to perception. I hypothesise that due to these selection effects favouring overconfidence, we live not in a meritocracy, but in what I call a confidocracy. With so many aspects of a person’s success in their career and life determined by the evaluations of others (often others who lack the subject-specific knowledge to properly evaluate competence in one’s niche), the selection pressures favour one who is overconfident.