We spend our days endlessly repeating simple tasks, and even outside of work we refuse to grapple with higher order ideas and concepts. Politics has been reduced to squabbling over petty resentments, a kind of spectator sport. Even our art has given up on the profound, simply packaging up nostalgia and spectacle to be sold back to us. We cannot call ourselves grown men if we act like infants.

Tag: Politics

-

The Growing Illiberality of Liberalism

At the core of the liberal philosophy which guides our modern societies are two principles – free people and free markets. It has generally been assumed that these are in harmony. But as the populist consequences of the GFC continue to reverberate through our world, establishment liberals are being forced to choose between the two. Time after time, unelected officials have chosen to protect the markets against the consequences of democracy in a way that lays bare their true priorities.

-

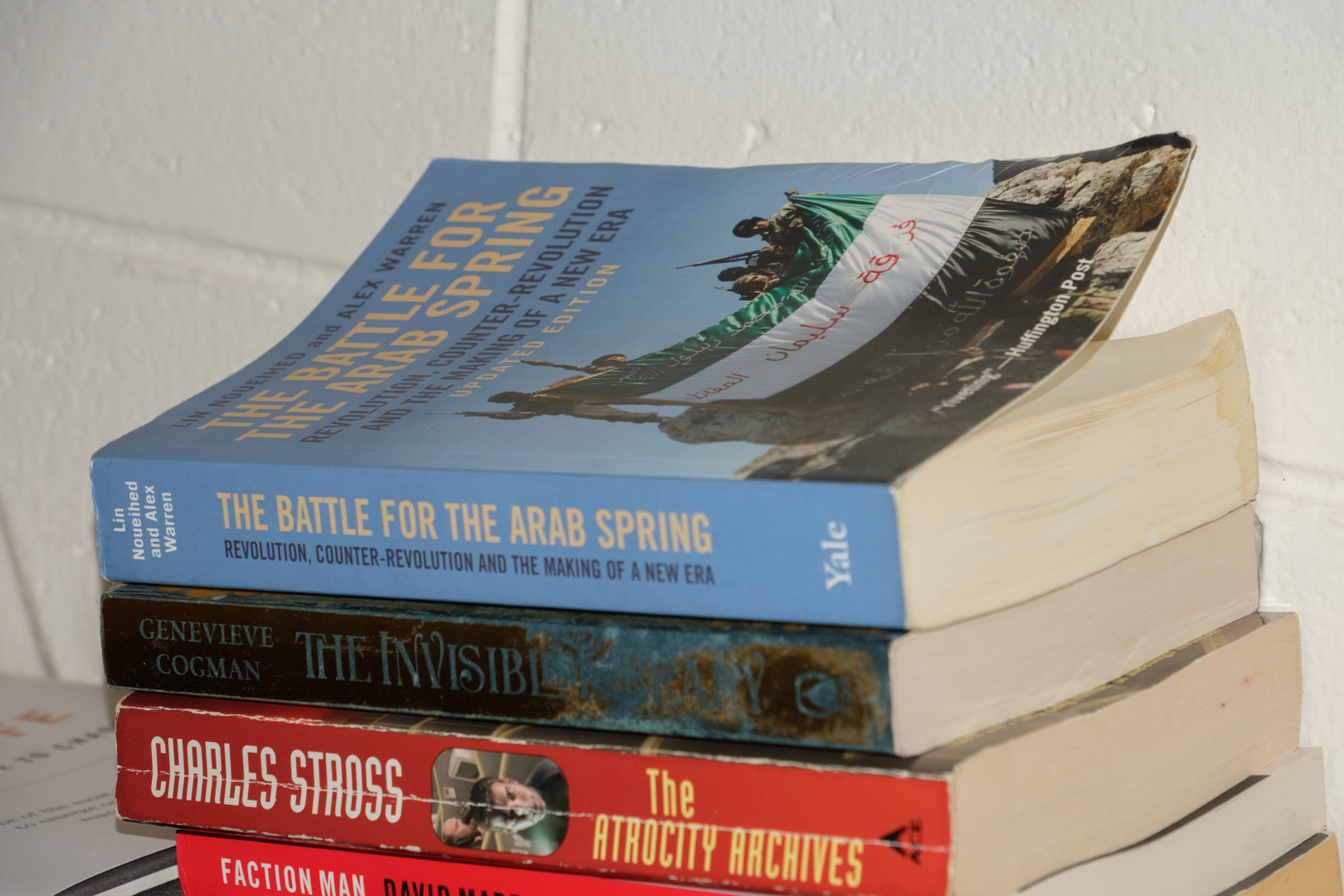

Lessons from the Arab Spring

The self-immolation of Tunisian vegetable seller Mohammed Bouazizi in late 2010 set off a wave of protest and revolution against stagnant dictatorships across the Arab world. Ordinary citizens stood up against their tyrants and forced them out with people power. Lin Noueihed and Alex Warren’s The Battle for the Arab Spring tells the story of these rebellions – a tale which should be heeded by those who seek a better world.

-

Financialised Capitalism

In the classic form of capitalism, companies competed to sell their products to customers with the aim of producing profits to fuel further expansion. Today, companies no longer need to make profits in order to command massive valuations – Elon Musk‘s Tesla is worth $US 48 billion despite accelerating losses to $2B last year. Making money is no longer a prerequisite for business success. Instead, these companies serve as stock market vehicles, catering to the whims of investors rather than customers. This serves to remove any measure of control ordinary people might have been able to impose upon corporations through their choices in the market.

-

Indentured Servitude

Back in the bad old days of slavery and serfdom, there was a class of people who weren’t quite slaves, but weren’t free either. These indentured servants were tied by contract to serve a particular master as slaves, but only for a specified period (typically 3-7 years). Folks who were desperate for passage to the Americas or who had accumulated debts beyond their ability to pay would sell themselves into virtual slavery with the hope of a better life after their period of bondage ended. South Sea Islanders were coerced into similar contracts to labour in Queensland in the late 1800s, long after such arrangements were outlawed for white folks. But were they actually outlawed, or just transferred into another form?

The Employee does hereby agree to faithfully serve the Company for three years from the date of his landing in the land of Virginia, there to be employed in the lawful and reasonable works and labors of the Company and their executives, and to be obedient to such managers as the Company shall from time to time appoint and set over him.

– From the indentured servitude contract of Robert Coopy, 1619, edited to modernise

The life of an indentured servant was nasty, brutish and short. Despite the incentives present at the end of their contract (the transfer of land and often supplies for a year), these folks had no freedom, being tied to the whims and punishments of their masters. It may have been a better life than that of a slave (who gradually replaced them in the 1700s), but indentured servants were forced to work from dawn to dusk and could be sold between masters like commodities.

Whilst employed by the Company, the Employee must devote his or her whole time and attention to the business of the Company as required and must not, without the prior consent of the Company, engage in any other activity or employment.

The owner had complete control of a servant’s life and the backing of the state to ensure compliance against any runaways. Servants internalised the virtues of the Protestant work ethic to justify their own bondage, but masters also provided plenty of extrinsic motivation through harsh discipline.

The Company may use surveillance personnel in strategically located internal and external areas of the plantation to monitor movements. Guards will operate continuously and surveillance will be ongoing.

Under this strict surveillance, servants toiled from dusk until dawn for the benefit of their owners. Everything that a servant created would be the property of their owners, as was the servant themselves. The ultimate alienation.

The Employee acknowledges and agrees that the Company is the sole and exclusive owner of all rights including without limitation copyright throughout the world and all journalistic, literary and artistic work created, conceived, developed or acquired, in whole or in part, by the Employee, in the course of the Employee’s employment with the Company, however and whenever created or conceived, whether solely or jointly with others and whether during work hours or otherwise.

Even once freed, indentured servants often found that their supposed rewards were dependent on the whims of their owners. Their parcels of land might be subject to extortionate rents, the supplies provided were often minimal, and their low status and injuries suffered during their servitude restricted their opportunities.

For the duration of the Employee’s employment with the Company and for 6 months thereafter, the Employee must not on his or her own account, or on behalf of any other person in whatever capacity (without the prior written consent of the Company in its absolute discretion) participate in any business similar to the business of the Company or any Related Company.

But apart from our dear friend Robert Coopy up the top, these quotes are not from the contracts of indentured servants. They are from an employment contract which crossed my desk today (and have been lightly edited so as not to give the trick away with modern boondoggles). I am to be paid much better than poor Robert was for my services, but the conditions of servitude never went away.

A forcing-up of wages would therefore be nothing but better payment for the slave, and would not conquer either for the worker or their labour their human status and dignity.

– Karl Marx, The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844

Whether I sell myself for a million dollars or a loaf of bread, I am still selling myself. A modern salaried worker has no right to an 8 hour day, no right to the fruits of their own labour, limited rights even to sell their services elsewhere. No doubt we have better material conditions than the indentured servants of the 1600s, but on a philosophical level the conditions remain the same. The employing class still own the working class. Our labour is not ours. The products of our labour are not ours. We are not ours.

-

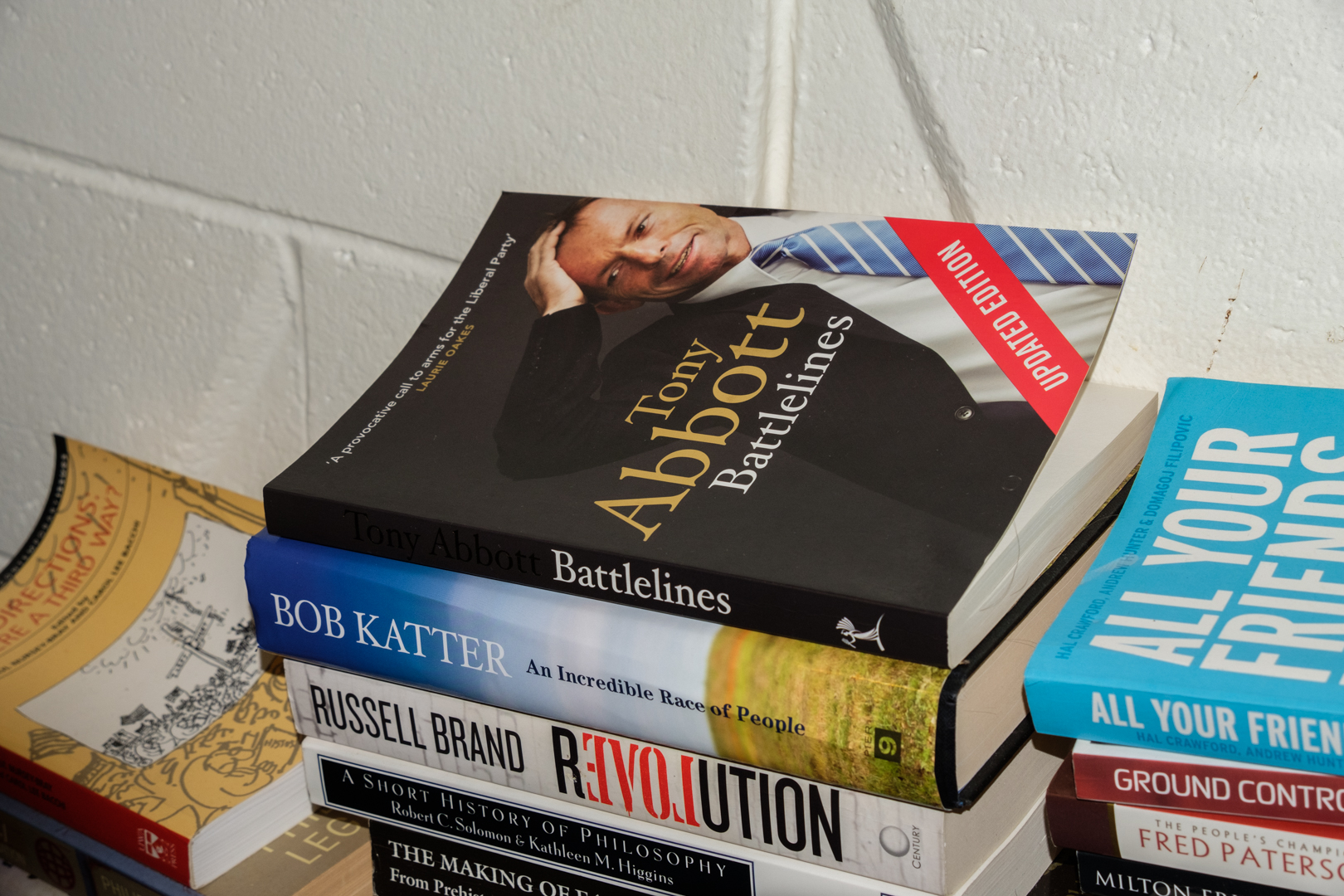

Book Nook – Battlelines by Tony Abbott

Tony Abbott is not a smart man. Beneath the thin veneer of political savvy lies a man whose politics are solely derivative of an enormous ego. Tony personally identifies with conservative institutions like the monarchy, family and church, and so his inability to perform any kind of self-reflection extends to these as well. This is a man born in privilege whose greatest challenge in life was when the media once scrutinised him and who claims that being a politician is as hard as a soldier. A man who has been handed every job he’s ever had by an old boys network, yet asserts that folks on disability pensions need more incentive to work. The 28th Prime Minister of Australia.

(more…) -

The Debt and Austerity Narrative

Four years ago, the Liberal government assured us that hard budgetary cuts were required to tame a “debt and deficit disaster“. Since then, that same government has increased our net debt by more than 55%, or $129 billion. When tonight’s budget is released, Treasurer Scott Morrison is expected to find money for tax cuts, both for personal incomes and to fund the corporate tax cuts for the big businesses which have yet to pass through the Senate, while the budget remains in deficit. The Medicare levy increase which was to fund the NDIS has been scrapped. If our national debt is such a crisis, then how can we afford such cuts to revenue?

Conservatives the world over have found success through a reputation for responsible economic management. US Republican Speaker Paul Ryan forged a reputation as a proud fiscal wonk, urging difficult choices and cuts to spending in order to tackle America’s debt. Yet once his party swept into office, he enthusiastically supported President Trump’s trillion dollar tax cuts, blowing a hole in the deficit and condemning government debts to grow even further. In the Eurozone, severe cuts to public services have been justified by a demand for austerity in the face of rising national debts, yet this has been accompanied by cuts to corporate taxes. Across the globe, this concern for national debts only ever seems to translate to cuts to public services, not any other budgetary options. This is not by coincidence, but by design.

The fear of debt is a powerful motivator for citizens, with numbers beyond their comprehension and an implicit intergenerational unfairness. This fear has been captured and amplified by conservative politicians in service of their ideology. Paul Ryan is a follower of Ayn Rand, and her sociopathic vision of society run by and for business. He doesn’t actually care about reducing the national debt, as his actions have shown. He cares about reducing the role of government and increasing that of private enterprise.

For those who want to eliminate public services, the idea that the government is spending too much is a potent one. Cuts to any and every program can be justified if we run the risk of credit default. But these cuts do tend to decrease government spending (even if they can sometimes be outsourced directly to the private sector instead), which risks ruining the narrative. If the government has enough money, then the plebs might demand it be spent on public services, which remain resolutely popular. So as cuts are made to services, they must also be made to government revenues through tax cuts, concessions and business handouts to make sure that the budget is in a permanent state of crisis.

Though our government has no ideologues of the Paul Ryan level, the paucity of ideas developed within our Liberal Party meant that eventually these American strategies would be employed here. Our conservatives may be egotistical morons, but they can see how well the politics of austerity have worked to cut public services and to justify tax cuts to their corporate mates, both in the US and Europe. So with more money found within the budget, it must be cut from revenues lest it risk ruining the crisis narrative.

With an election looming and polling remaining in favour of the opposition, the Liberal Party have flagged a specified maximum tax to GDP ratio of 23.9%. This would tie the hands of any incoming government, ensuring deficits and running up Australia’s debts to the higher levels seen in other developed countries. It is a very savvy political move which could enshrine the debt austerity narrative for a generation as our population ages and requires more spending on health and pensions.

While I expect this obfuscation from the conservative side of politics, the Labor Party’s response demonstrates again how they have been swept away by the narratives of neoliberalism. Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen could have used the money which has been found in the budget to support an increase in the criminally low Newstart benefit, as his party members have been agitating for. With more money flowing into the economy from those who spend every cent they get, growth and inflation would increase, improving the budget position as a side effect of good policy, not a goal. But instead, Labor has bought into the debt austerity narrative, demanding that the government be more fiscally conservative and ensure bigger surpluses, sooner.

The national budget is not like a household budget. A government which prints its own currency and can set its own taxes upon its own economy cannot be run the same way as a household with simple income and expenses. This is not to say that debt is entirely unimportant, but simply that there are far more policy options available than simply running surpluses in order to reduce debts. Between the end of WW2 and the end of the Callaghan Labour government in 1979, British public debt dropped from 250% of GDP to less than 50% through growth and inflation, despite running deficits in most years.

Austerity is a choice, not an economic necessity.

-

Self-Commodification

In our market society, every thing is transformed into a commodity to be bought and sold. Buyers and sellers meet to trade not only petrol, but also fine art and literature. We also sell ourselves on the market, renting out our lives to employers. In our current epoch these commodities are not just sold, but actively moulded to better suit the demands of the market. Not only do brewers adjust their formulations based on sales, but we shape ourselves to better fit our perceptions of what the market demands.

Who are you? You are your self – the central tenets of your own identity. But your self is not set in stone, it is shaped by your choices and experiences. You aren’t the same person you were at age 18.

There are some aspects of your self that you share freely with the world and others which you keep close to your chest. This is normal, humans are naturally duplicitous creatures. The self you show to the world exerts a pressure on your core self, refining your values and choices through reflection. In the age of social media, our selves have been opened up to the world in unprecedented ways. Every post, every interaction is subject to public scrutiny. This scrutiny is not just from our peers, but also from the myriad of market actors which can have profound impacts upon our lives.

On social media or in life, every interaction may be the start of a path to that elusive good job. Advertising your capabilities as a worker could lead to that opportunity, but conversely displaying unsuitable traits may freeze you out. So a pressure is exerted on what you say, the company you keep and the activities you undertake. Do you attend the gig or the seminar; talk about work or politics? The invisible hand of the market directs you towards those activities which enhance your personal brand and thus market value.

Your work doesn’t finish when you leave the office, but instead becomes a filter through which you mediate your life. You worry about whether a particular education makes you employable, about whether a gap in your resume will prove insurmountable. Instead of drinking with friends, you network with professional colleagues.

Your performed self is alienated from your actual self, driven by the need to hustle for every opportunity and avoid anything which might cast you in a negative light next time you make an application. As you continue to perform, your internal self moves away from that actual model, warped by the demands of the market. In this grim late capitalist world, your self is increasingly concerned with maximising its worth to employers rather than with self-actualisation.

By this point, you have completed the transition from person to commodity. You are no longer defined by your individual character or values, but instead are simply interchangable wage labour, another bottle of cola trying to appeal to a customer with snazzy branding or a low price. What is LinkedIn but a human supermarket where recruiters can choose among millions of wage labourers?

In the Soviet supermarket, there were only two kinds of worker available, peasants and bureaucrats moulded by the police state. In the neoliberal supermarket, there exists a rainbow of worker brands. But they all taste the same, all shaped by the market towards a kind of dull positivity and competence with spreadsheets.

The power of the market is in shaping people and their actions with incentives rather than gulags. The prospect of material riches is a powerful motivator. The market does not force you, but rather encourages you to turn yourself into a commodity. But you do not have to accept this. Even without abolishing markets, a skilled worker can still hold true to their values.

-

The Case for Universal Basic Services

How do we solve the coming decimation of jobs through automation? The solution of a Universal Basic Income has united both Silicon Valley libertarians and social democrats, offering a guaranteed income to every citizen. But the practical and political issues with the UBI mean it will only serve as a temporary salve for the underlying problems. Instead, progressives must argue for Universal Basic Services, drawing on the history of publicly provided health and education services to build a state fit for the 21st century.

Automation will put between three and five million jobs at risk in Australia by 2030. Some new jobs will be created, but the rise in baseline unemployment since the Second World War will continue, putting millions out of work. This structural change will require adjustment to welfare systems, or risk severing the social contract and plunging the reserve army of labour into wretched poverty.

The idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) has been around for some time, championed by Hayek and Friedman on the right, as well as Martin Luther King on the left. The idea is that every citizen would receive a basic stipend paid by the government. This would be paid for through the elimination of existing targeted welfare systems and tax increases on the rich to counteract their portion of the UBI. But because this idea has come separately from the left and right, there are two competing views of how the program should be implemented.

The social democratic version of a UBI would provide each citizen with enough money to fulfill their basic needs. Each person could then spend this income on the market, and this consumption would circulate through the economy, providing customers for businesses and allowing each person to allocate their money to maximise their own utility. Systems like the NDIS would remain in place to ensure that those with exceptional needs have those met. The social democratic UBI would keep everyone from absolute poverty and desperation. By ensuring that people’s basic needs are met, it would also allow more risk taking by entrepreneurs and artists.

But the social democratic vision of a UBI is not the only version of this policy. The conservative vision of a UBI is as a trojan horse to dismantle the welfare state. Milton Friedman didn’t advocate what he called a negative income tax in order to eliminate poverty, but to serve his ideology of small government. Under a conservative vision, the basic income level could not be sufficient to live on, but would be kept as low as possible (like the dole) in order to ensure recipients are desperate for work. All other welfare programs would be abolished, meaning that the desperation for work would extend to the retired and injured. The UBI would also serve as a cudgel for cutting other government programs – for instance replacing universal healthcare with an increase in the UBI to allow for citizens to buy their own health insurance.

In a two party democracy like ours, these competing visions of a UBI would clash, providing conservative governments with justification for slashing public welfare and services whenever they are in power. For all the good intentions of a social democratic UBI, it cannot fail but be corrupted by the libertarian right. In a policy contest between social democrats who want to maintain welfare at a low but livable level and conservatives who want to push it as low as possible, the social democrats cannot win. The collapse in the level of unemployment and student benefits in Australia demonstrates this well.

Even discounting the political problems, there are practical issues with a UBI as well. The amount of funding necessary is substantial – if the current welfare spend was diverted entirely to UBI, it would provide each person with a little more than $6000 per annum, thus requiring spending to be quadrupled in order to reach the poverty line. Core to the idea of the social democratic UBI is to fund it with tax increases on the rich, but a $500B per year tax increase would be tough for even the most radical in the Labour Party to support. It is more likely that the UBI is set to a much lower level, ensuring that it does not meet people’s living needs and functions like a conservative UBI in practice.

By relying on the market as a mediator, the UBI also introduces a slew of other problems. Much like first home buyers grants only serve to pump up the prices of homes, there is a real risk that a UBI will just end up in the pockets of landlords who can set higher rents at the bottom end of the market. The profit seeking motives of market intermediaries like this mean that a cash grant has to be higher than what would be required for the government to fund the services directly.

So why not provide Universal Basic Services instead? The state could provide basic housing, food, transport and communications in addition to existing healthcare and education services. The public sector already has recent experience in providing services in all these areas, from social housing to public transport and pre-privatisation telecommunications networks. The healthcare example demonstrates the cost savings which are possible through public services rather than those run for-profit – the UK’s NHS costs less than half that of the private US system. This would allow the services to be set at a genuine living standard while keeping tax increases to palatable levels. All the benefits of a social democratic UBI, but at a much more affordable cost.

Providing a non-market alternative in these basic areas would also have other benefits. The poor would no longer be anxious about whether they could afford the necessities, as these would be guaranteed. The public provision of these services would have unexpected benefits, like eliminating food deserts and homelessness. It would also help to combat alienation, allowing creatives to meet their basic needs without pandering to the whims of a fickle market. It may prompt a rethinking of the central role which markets play in our society.

Those who wish to seek their riches and luxuries on the market would still be able to, but those with other priorities would be freed from the drudgery required to make rent. Without this Sword of Damocles hanging over the worker’s head, they will be able to push harder for wage rises, whose stagnancy has been decried by even the Reserve Bank. In a society where basic needs are guaranteed one can forsee some in the creative class eschewing the market entirely, enriching the lives of all. Entrepreneurs would not need to set aside funds for their own survival, helping startup businesses become established and providing a boost to innovation.

Universal Basic Services may reduce the incentives for people to undertake menial labour. Some would see this as a negative. But in a world of increasing automation, the demand for low skilled workers will contine to fall. UBS would make it easier for workers to retrain and build their skills in the new fields demanded by the market, helping fit them to the skilled work available. Critics will decry the program as enabling bludgers to watch TV all day, but is this any less valuable to society than them working as telemarketers instead? In an automated world with less demand for low skilled labour, we need to reconsider the nature of unemployment. I believe that the vast majority of people want to do socially useful work, and if this is community volunteering or their own creative projects rather than the alienating wage labour they are forced into at present then all the better for them and us.

Politically, there is no right wing case for the state to provide these services. So there would be no squabbling and compromise between the left and right over the level of service provided. History shows that once implemented, universal public services are very hard for any conservative government to repeal. By their universal nature, voters experience these services and understand their value – the whole population cannot be decried as ‘welfare queens’. Consider how the Labor Party was able to fight the last election solely on saving Medicare from privatisation, even though the Liberal Party had no such policy.

There is strong support for increased public spending funded by taxation on those who can afford to pay. Without action in advance of the job losses caused by automation, we risk severing the social contract and leaving swathes of the population in abject poverty. Universal Basic Services are a radical idea, but one whose time has come.

-

Beneath the Corporate Mask

Companies deploy elegant public relations masks in order to appear a positive influence on our society and lives. BP claims to deliver services that “help drive the transition to a low carbon future“. Northrop Grumman are “committed to maintaining the highest of ethical standards, embracing diversity and inclusion, protecting the environment, and striving to be an ideal corporate citizen in the community and in the world.” But beneath the hollow sheen of advertisements and corporate branding is an ugly demonstration of what is really important to the corporations who run our lives.

The infamous vampire squid – Goldman Sachs – released a report to investors on gene therapy developments a few days ago. In it, their analysts raised concerns with the profit potential of such companies, asking “is curing patients a sustainable business model?” Treatments like gene therapy do not offer the recurring revenues of the pharmaceuticals currently used, and “could represent a challenge for genome medicine developers looking for sustained cash flow.”

Those investors who can afford the fees of Goldman Sachs don’t want platitudes about corporate responsibility. The lives of those who might be saved with new innovations have no importance when there are profits to be made. These ghouls can extract more money from a patient who needs to take a pill every day for the rest of their lives than from one who can be fixed with a single treatment. The patient’s entire future earnings are available to pilfer, rather than just the savings they may have accrued to date.

This rigid focus on money and profits regardless of the consequences is not merely confined to corporate investors but has spread throughout our society. While public relations departments might paint a different picture, those who wield corporate power continue this rigid focus on economics. Petrochemical giant BP’s submission to drill for oil in the Great Australian Bight was recently unearthed, in which their real vision of the world was laid bare.

BP claimed that in the event of an oil spill, “in most instances, the increased activity associated with cleanup operations will be a welcome boost to local economies” with no social impacts. This displays the very same worldview as the Goldman Sachs report – that the only consideration is monetary. The massive environmental degradation which would result from any oil spill is of no importance, except that the locals might be benefit from temporary jobs cleaning the slick from their once pristine beaches.

Within the ideology embedded in our society, life is simply a game where each player’s score is measured in dollars. Profit isn’t just the most important thing. It is the only thing.