When it was first released to arcades in 1980, Pac-Man created a new Maze Chase genre which was radically different to the sports, racing and shooting games which had come before it. This became a breakout pop-culture hit with appeal across genders to such a level that two seasons of a Pac-Man TV shows were produced. Even today, Pac-Man’s iconic visage is still one of the most identifiable gaming figures. Yet by 1985 the genre was in deep remission and by 1995 it can be fairly argued dead, except for Namco’s own Pac-Man remakes and re-imaginings. Adventure games went into remission and came back. 2D shooters (ala Galaga) are niche, but still being made. What was it about the Maze Chase genre which led to such an immediate boom and bust cycle?

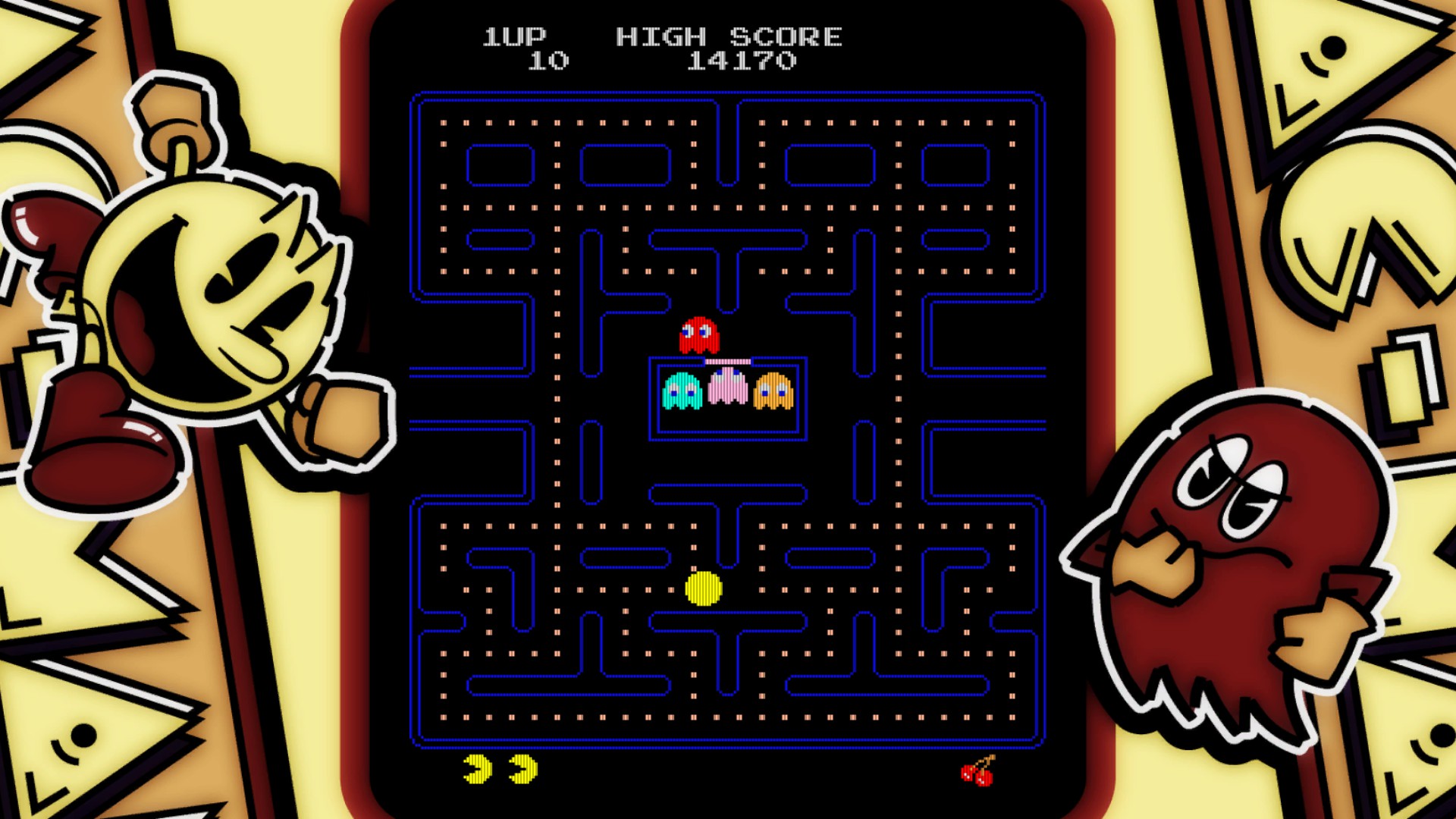

The setup of Pac-Man is familiar through its place in popular culture, even if like me, you’ve never actually played the game before. Move Pac-Man around to eat all the dots and avoid being eaten by the ghosts which pursue him. Eating a large power pellet will turn the tables and let you eat the ghosts. This is a great little bit of mechanical storytelling, it feels great to get revenge on your tormentors. But what I didn’t realise until playing is that Pac-Man actually includes primitive cut-scenes between levels, showing this reversal of fortunes.

For a 1980 arcade game, this is pretty gosh darn impressive. In fact, Pac-Man feels much fresher than its Arcade Game Series counterparts Galaga and Dig Dug, despite actually being an older game. I’d posit that this is due to the genre’s death, which makes Pac-Man feel original, whereas Galaga feels like a simplified version of the shooters which have come since. Pac-Man is still a blast in short bursts today, with lots of quick decisions, spatial awareness and predictions of enemy movement required in order to navigate the maze efficiently and avoid the ghosts. That feeling when you pop a power pellet and chow down on the four ghosts that have been menacing you is fantastic. So I wonder whether the genre died because Pac-Man perfected it as soon as it was born?

For a 1980 arcade game, this is pretty gosh darn impressive. In fact, Pac-Man feels much fresher than its Arcade Game Series counterparts Galaga and Dig Dug, despite actually being an older game. I’d posit that this is due to the genre’s death, which makes Pac-Man feel original, whereas Galaga feels like a simplified version of the shooters which have come since. Pac-Man is still a blast in short bursts today, with lots of quick decisions, spatial awareness and predictions of enemy movement required in order to navigate the maze efficiently and avoid the ghosts. That feeling when you pop a power pellet and chow down on the four ghosts that have been menacing you is fantastic. So I wonder whether the genre died because Pac-Man perfected it as soon as it was born?

In the years immediately following Pac-Man’s release, waves of clones and other Maze Chase games hit the arcades and shelves for the consoles of the time. This coincided with the great video game crash, so given that these others have since vanished into the ether its fair to assume they couldn’t hold a candle to the original. It is entirely possible that this wave of shovelware killed interest in the genre outside of the reliable Pac-Man.

Pac-Man’s success was also driven strongly from the American segment of the market, after an initially lacklustre launch in Japan. I’d suspect that with the rise of the NES and focus on Japanese audiences in the period after the aforementioned crash, this style of game which was such a hit with American audiences was a lower priority.

But these assertions don’t explain why the Maze Chase didn’t spring back once the time was right. Pac-Man itself is still a solidly fun game, and I’ll be interested to see a more modern take on it from Pac-Man 256 which I’ll get to later in this series. The mechanics are tightly tied into the single screen format, which was required at the time and may have seemed outdated if reinvented later. I wonder whether the cross-gender appeal even hurt the genre later – once the English speaking revival came about in the 90s, the charge was led by tough manly games like Wolfenstein and Duke Nukem. Perhaps the aesthetic of Maze Chase games just didn’t suit the ‘Boy’s Own Adventures’ which gaming had morphed into. It may even just be that the Maze Chase died too early, and so once the relentless push for new technology slowed in the 2000s, it was too old and out of designers minds. Certainly it was out of my mind.

This has been an interesting little trip into the past with Namco’s Arcade Game Series, but I’m really looking forward to having some stories and contexts to sink my teeth into. The next cab off the rank is Attractio, which looks to be a physics puzzler. I like both those things, so this should be good.